[CLOSE]

I

WETIN I DO DEY WIT BINI BRONZE?

Bini Bronze—dem be ogbonge show of di kain artistic sense wey Bini Artists dem get during di 13th reach 19th century. As e be, we no sabi di name of di Artists wey make di Bronzes, but we sabi say na Oba of Bini pay dem to create Bini Bronzes wit different different kain materials. Those olden days artist dem finish work for di Bronzes. Dem design di Bini Bronzes to carry spiritual meaning, wey pass ordinary eye. Some Bronzes dem design for Oba of Bini to use am invoke e ancestors or tok wit di Gods. Oda ones dem design to represent motor wey Oba of Bini fit use travel go anoda world. Or e go fit look like foto wey Oba of Bini go use remember e ancestors. Even sef, e get some Bini Bronze wey you go fit read as stories about Bini history, and plenty oda tins join join.II

WETIN I DEY DO?

Me, I just dey reason how di British wahala for 1897 scata di fine work wey our Bini artists dem dey do. Di reason why I dey tink am be say, na Oba Ovonramwen dey spoil Bini artists, dey give dem money, house and evri evri so dem fit create beta works for am. And na Oba dey control tins o, e no dey gree make dem show their talent for outside. So, wetin go happun when dia Oga on di top no dey again? How dem go see food chop? I hear say plenty of di artists dem waka from Bini, go oda villages wia dem start to dey farm, dey hustle.

But one question dey choke me: as dem turn farmers, shey dem still dey follow their art talent? Na im I go library to see if I fit find foto of any kind tin wey dem create during di time Oba no dey Benin. I find di tins am tire.

Di more I dey tink, di more e dey pepper me. British pipo dem record so many tins for Bini for dat time, but why e be say, dem no take foto of artwork wey dey Bini?

How we wan take know di true-true tori?

Na so I say, I wan know how dis 1897 kata kata affect one pesin for Bini. Di pesin name na "Iyoba Idia", wey be Oba Esigie mama. As my pipo tok am, Iyoba na warrior wey use im spiritual and political wayo to make sure say Oba Esigie stand gidigba. As Oba Esigie dey flex, e con tell Idia make she design Okuku hairstyle wey resemble im own, and say, make nobody else try am. Idia come do am, make e resemble Okuku mouth.

I dey tink about how di British wahala for 1897 scata Iyoba palace, so tay dem tell Iyoba make she no dey wear Okuku hairstyle because dem tok say she no be Iyoba for dem eye.

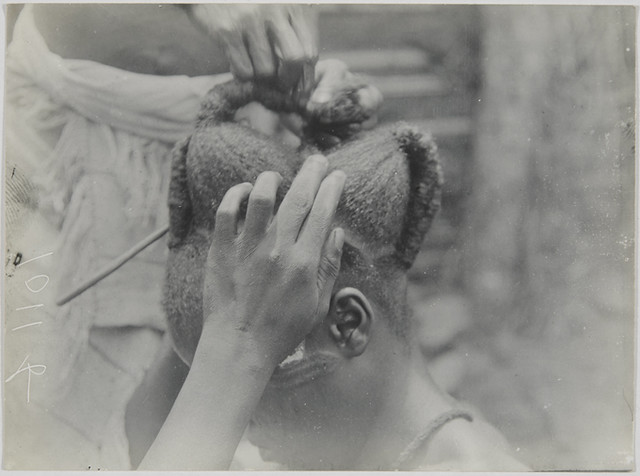

I dey tink about all di women wey dey make di Okuku for Iyoba.

I dey tink about all di artists wey helep make sure say dem knack Okuku hairstyle for Bini Bronze bifor British pipo land Bini.

Wetin happun to dem wen British tok say Iyoba no be warrior again? Wetin dem do wen dia madam no dey?

E possible say all of dem start to dey make Iyoba hairstyle for man pikin? Wen Oba alreadi tok say make dem no do am?

Dem make di Okuku?

If dem do am, wetin e look like?

Na why I tok say, make I start one project wey I dey call Igùn. For Bini, dem dey call craftmen wey dey make bronze, "Igùn". And, for Bini sef, area dey wey dem call Igún street. Di tin wey I dey do wit Igùn be say, I dey use technology wey dem call Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) to make feem and foto wey British pipo no care to record or show my pipo.

Wetin Artificial Intelligence (AI) be? Di wey I take undastand am: e dey behave like computa wey get sense. E fit make foto wey go make you reason if na pesin do am, abi na computa. How e dey work? No be Bini juju oh! Na Ogbonge engineers dey show am many foto wey human bin don make bifor. Dem dey call dis kain foto "data". And, dis data dey dey get am for internet. From Instagram oh. Facebook oh. Different Different kain website. And, di data wey di Engineers dey use no bi shikini one oh. E dey plenti, up to billions. As di AI dey look dis data, e dey understand di different different kain style wey dey inside di foto. Weda di foto na blue color. Weda e get mama or pikin. Weda di mama and pikin dey inside bus. Weda dey dey chop puff puff for di bus. Weda di bus get conductor. E dey undastand everi everi for inside di billions of foto. Afta e finish di lookri, e go com use di ideas wey e see, make im own foto wey go be like say na beta fotographer snap am.

Na im I say, make I kuku ma use dis AI, com make Bini Bronze wey I no fit find. How dat wan com take solve di real problem? E no go solve am O! And, me, I no get money to look for di Bini Bronze wey don loss. My concern be say, I wan remind my pipo say, di tins wey we no dey take eye see, wey book pipo no care about, or wey dem book pipo say no dey important, na di tins wey we go forget. And, me I no wan forget say sometin happen after dat 1897 kata kata.

I

WHAT ARE THE BENIN BRONZES?

The extraordinary Benin Bronzes are products of unnamed and unsung artistic geniuses who flourished under the patronage of the Benin royal court between the 13th and 19th centuries. Each Benin Bronze is meticulously crafted with iconography that defines its purpose in either sacred or secular contexts. They served varied roles: as conduits to facilitate dialogue with the Oba's (King's) ancestors and divine entities, vehicles for the Oba's interplanetary travel, portraits in honor of royal predecessors, visual records of significant events, and much more.

The Benin Bronzes not only showcase the unparalleled artistic brilliance of their creators but also bear witness to a colonial chapter in Benin's history. In 1897, the British Empire launched a military invasion of Benin Kingdom aiming to establish colonial control over the region and exploit its abundant natural resources, particularly the lucrative palm oil industry. This invasion culminated in the pillage of approximately 4,000 exquisitely carved ivory objects, metal casts in-the-round and relief, coral beaded jewelry, wood carvings, terracotta sculptures and a range of artifacts from Oba Ovonramwen's palaces, shrines and other communal spaces. Following this mass pillage, the artifacts were exported to England and auctioned to various private collectors and institutions. As a result, 160 Western cultural institutions have become custodians of the looted artifacts, collectively known as the Benin Bronzes.

II

WHAT IS IGÙN AI?

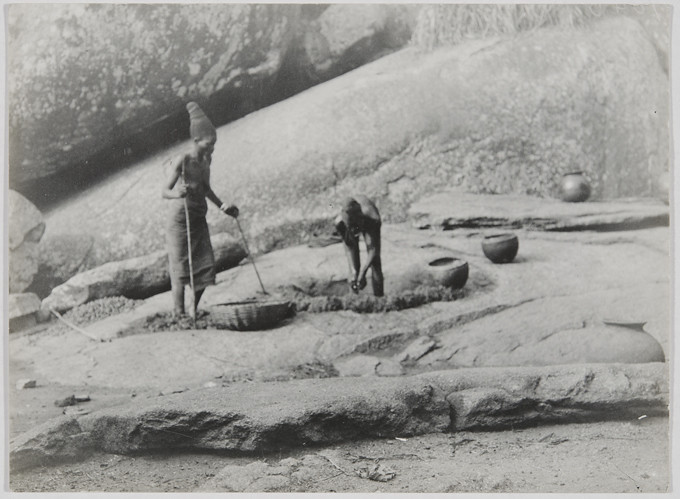

The 1897 invasion had a devastating impact on Benin's artistic landscape. British imperial soldiers razed the royal palace - a cultural complex that housed artist studios, residencies and repositories for imported art materials including the kingdom's bronze reserves. Amidst the chaos, Oba Ovonramwen—the Kingdom’s sole patron of the arts, was dethroned and exiled. The Oba’s exile prompted an exodus of artists from Benin city to satellite towns, where they forsook their artistic pursuits to engage in subsistence farming. This forced economic migration ushered in a 17-year (1897-1914) artistic recession — a period which lacks visual/archival records.Igùn is my attempt to answer a question about this dearth in documentation: What artifacts might have been produced during the 17-year artistic recession?

In Igùn: Prototypes I—IX, I leveraged the capabilities of StyleGAN2, a machine learning algorithm, to create a vast and varied collection of speculative artifacts. This process involved fine-tuning each algorithm with a dataset of looted Benin Bronzes - all curated from Western museums. No single prototype is designed to definitively answer my research question. Instead, my objective is to delve into the oft-conflicting artistic facts, and fictions that pervade this period.

III

IGÙN: PROTOTYPE X

THE CHICKEN'S BEAK BY MINNE

ATAIRU

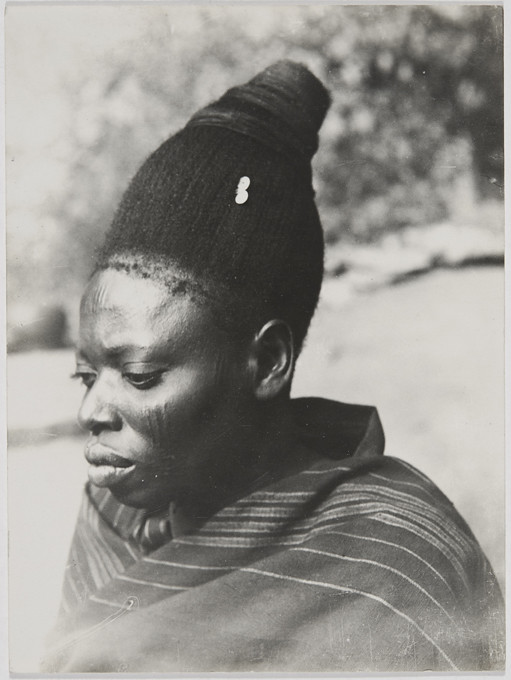

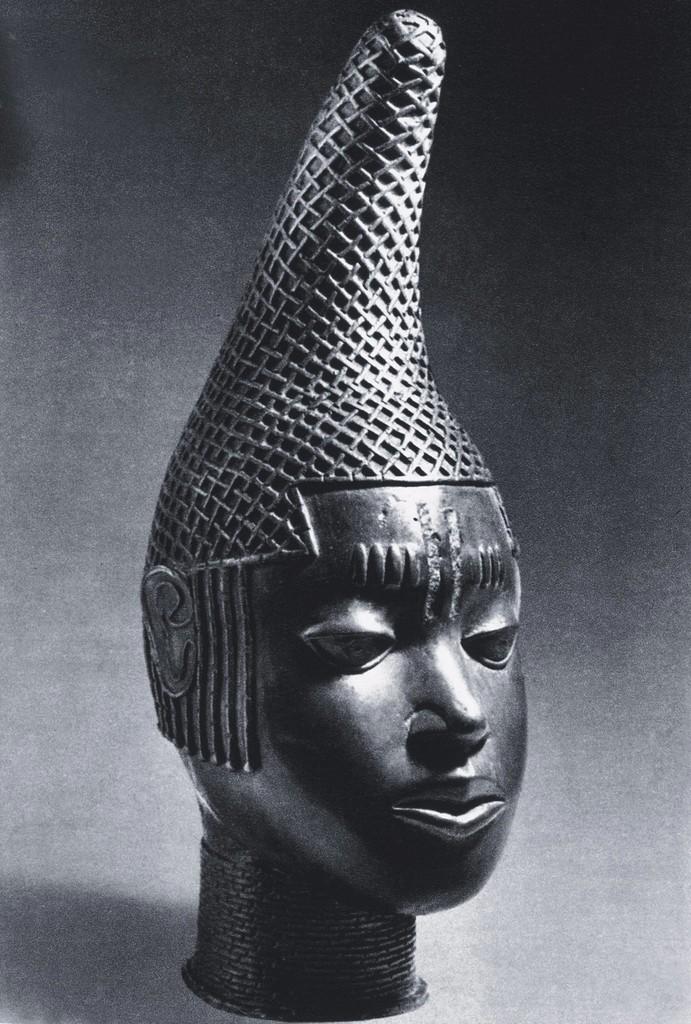

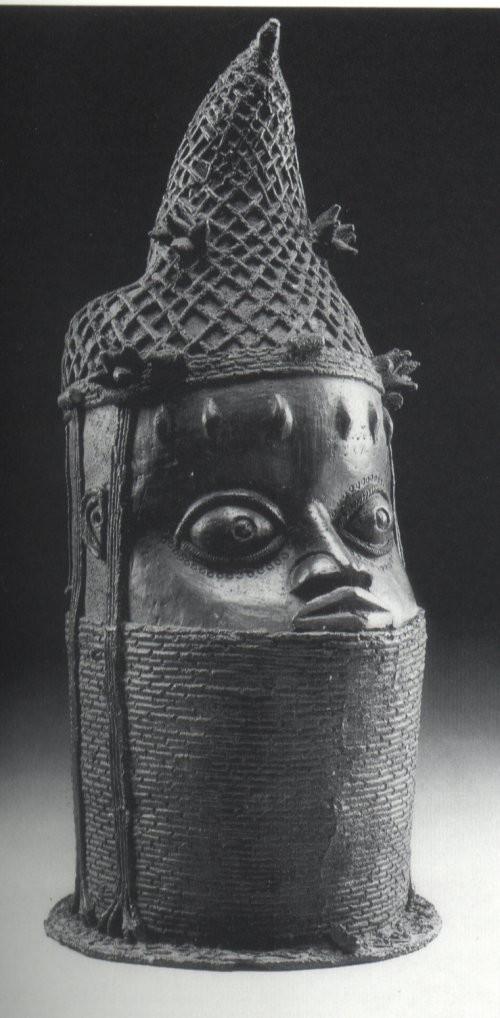

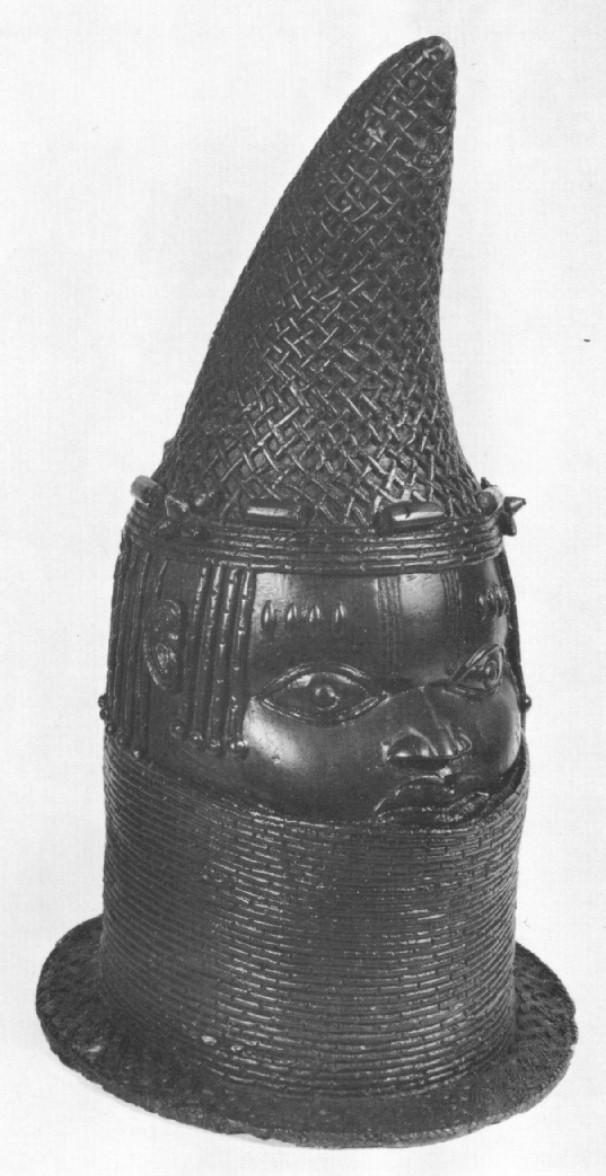

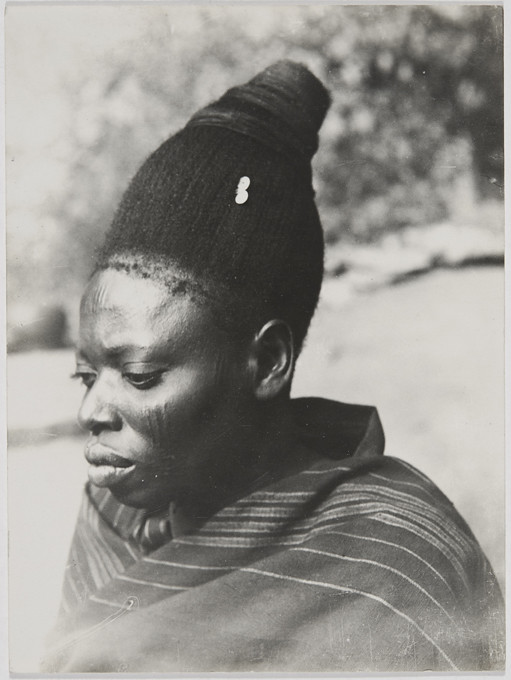

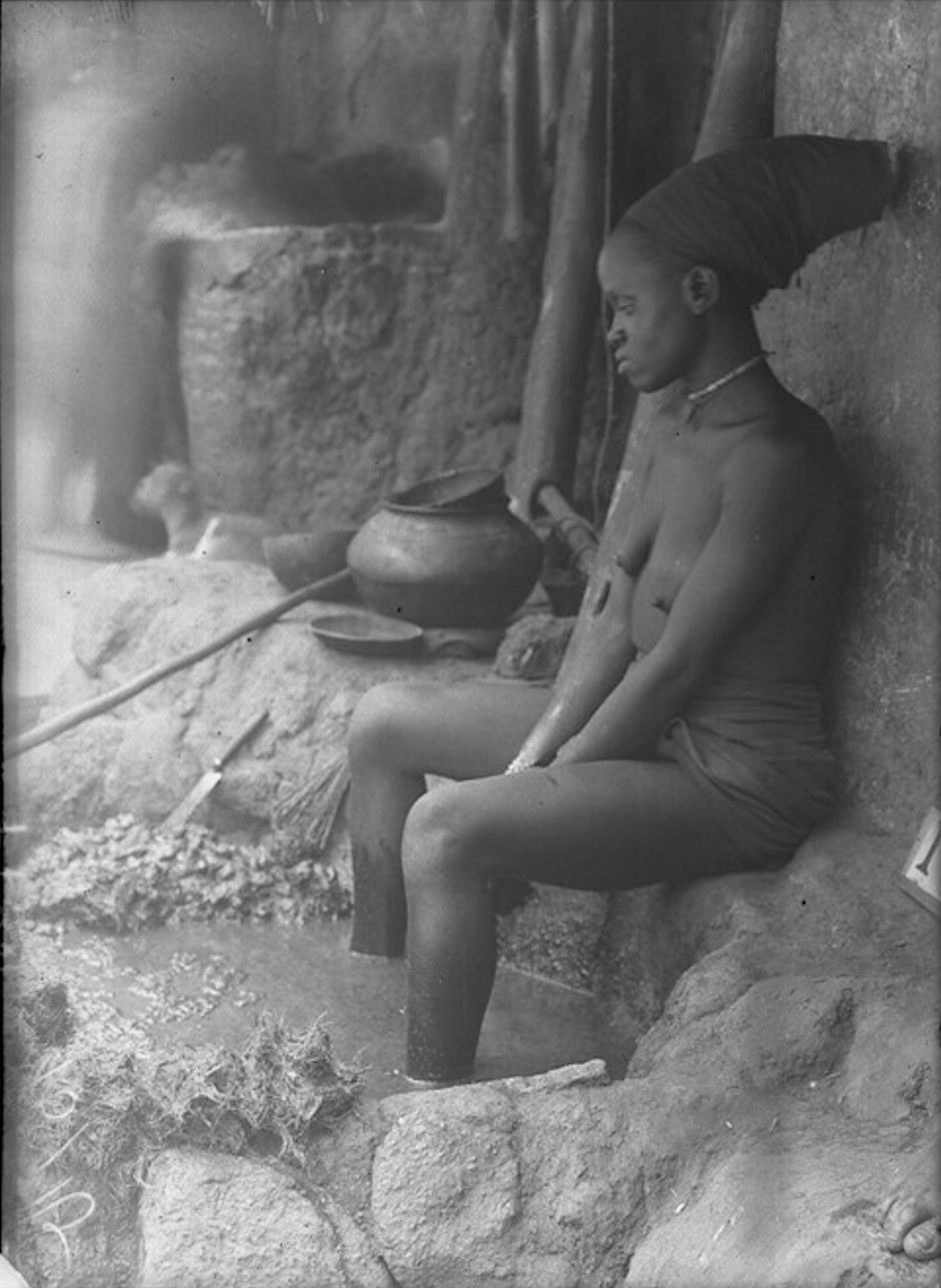

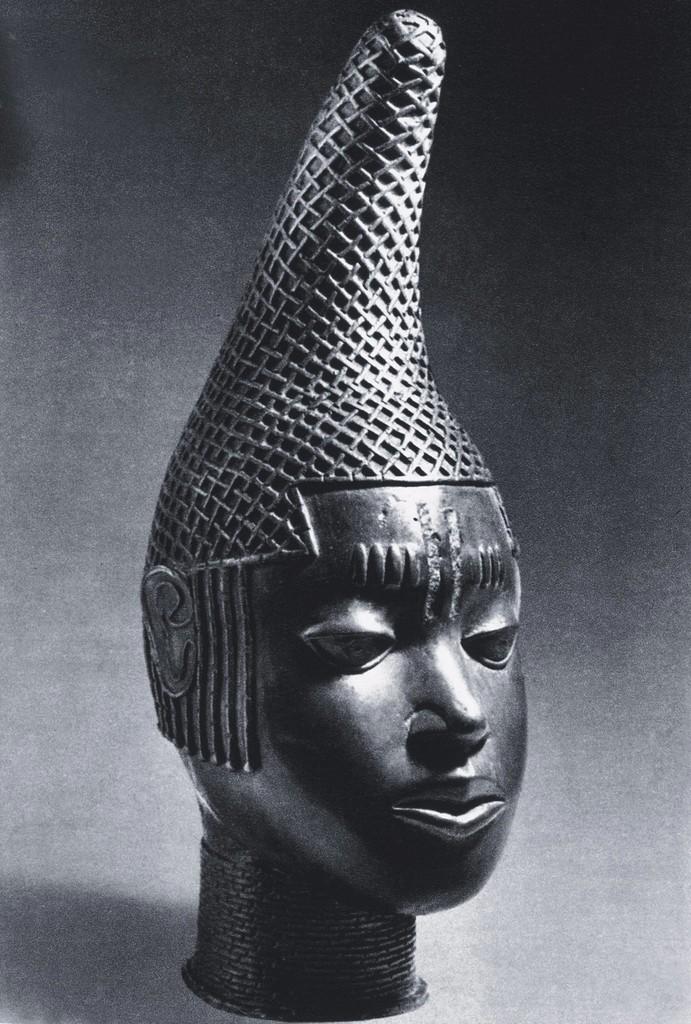

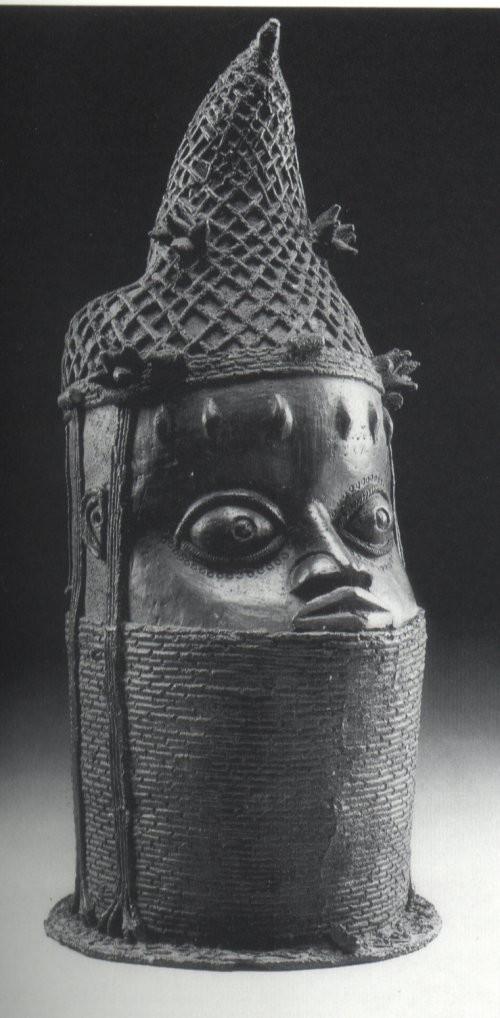

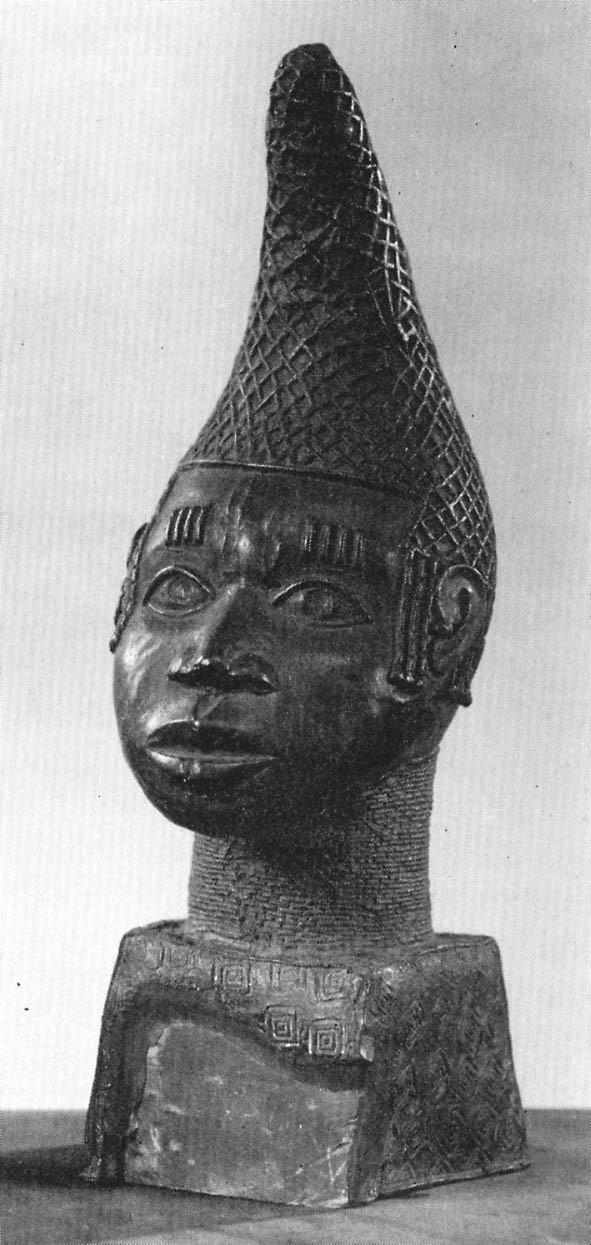

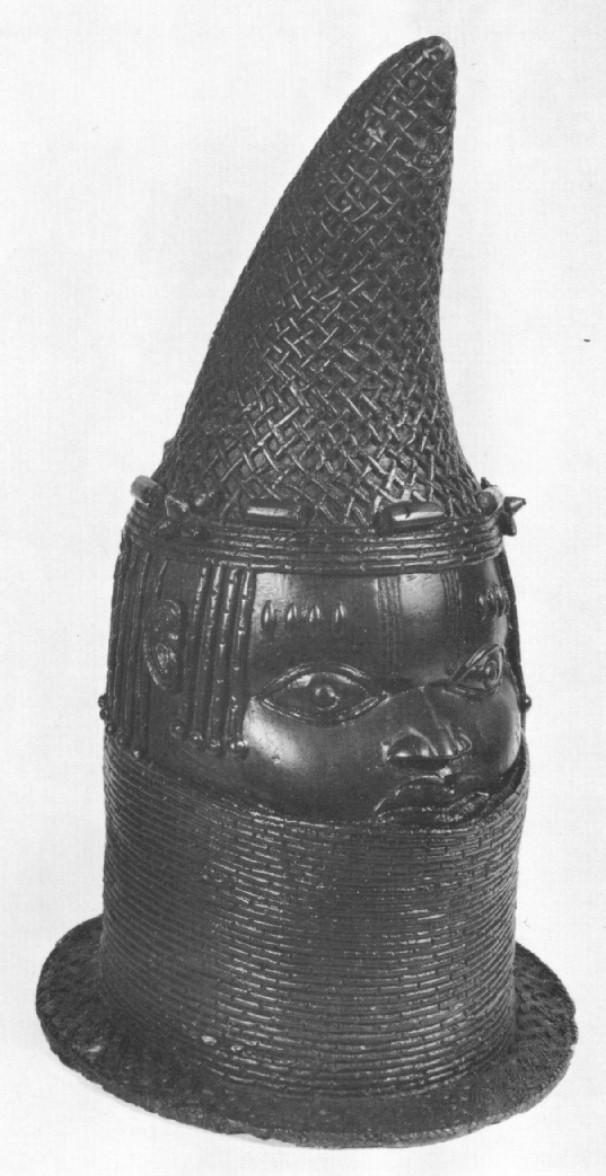

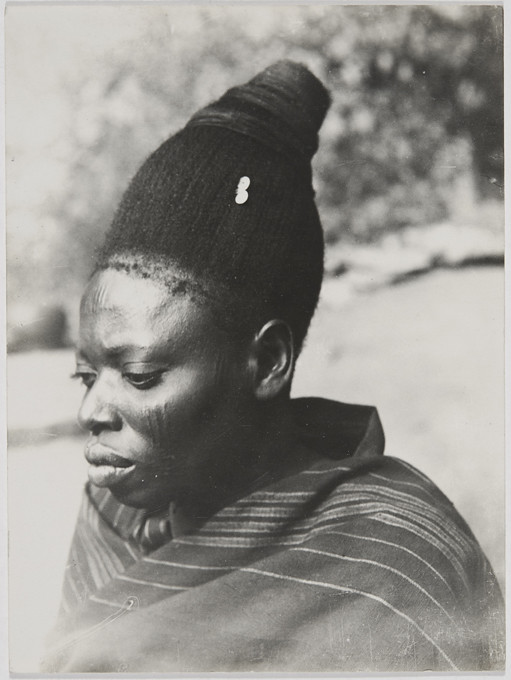

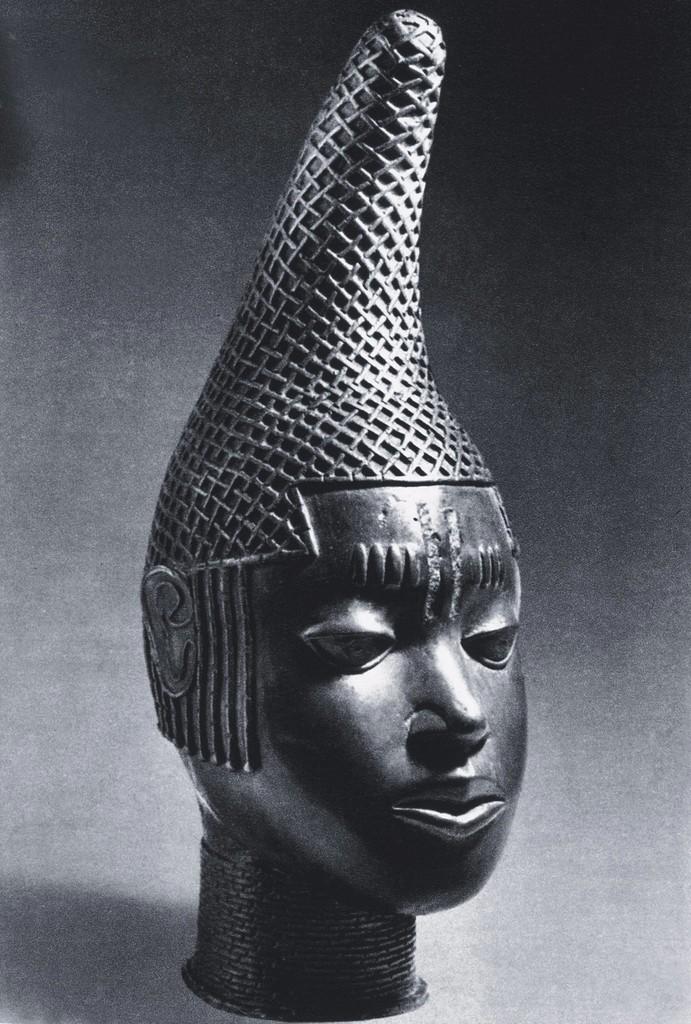

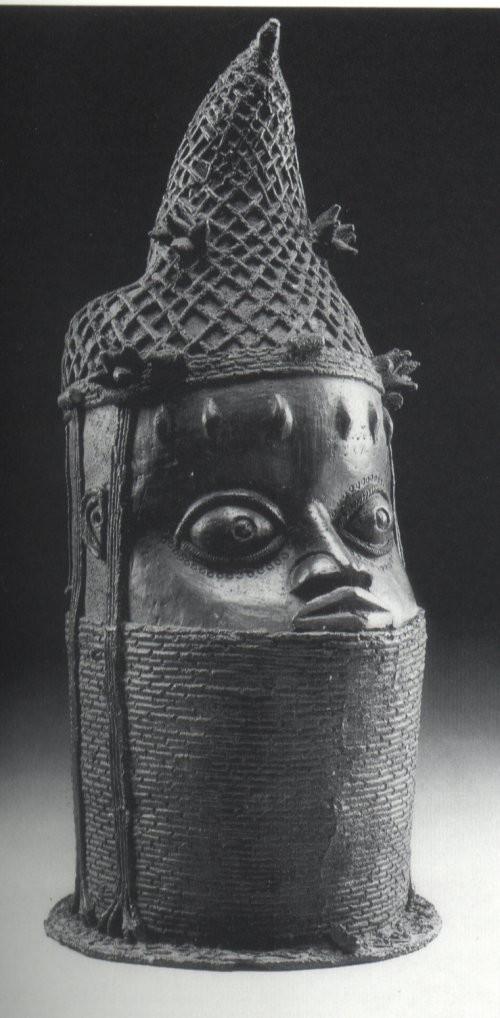

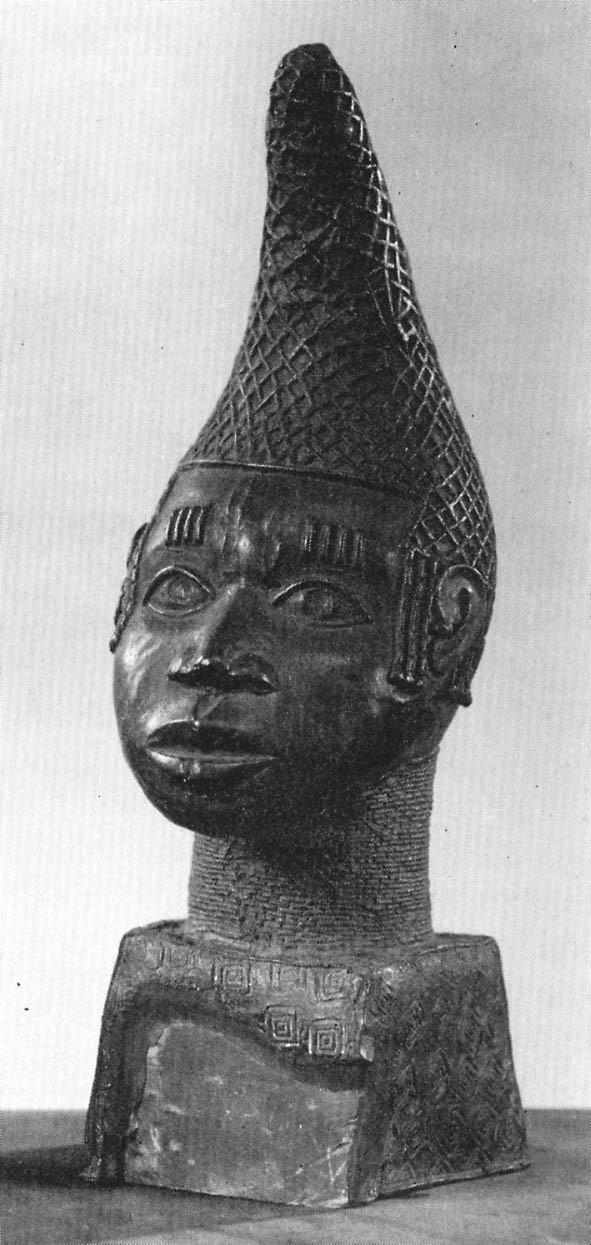

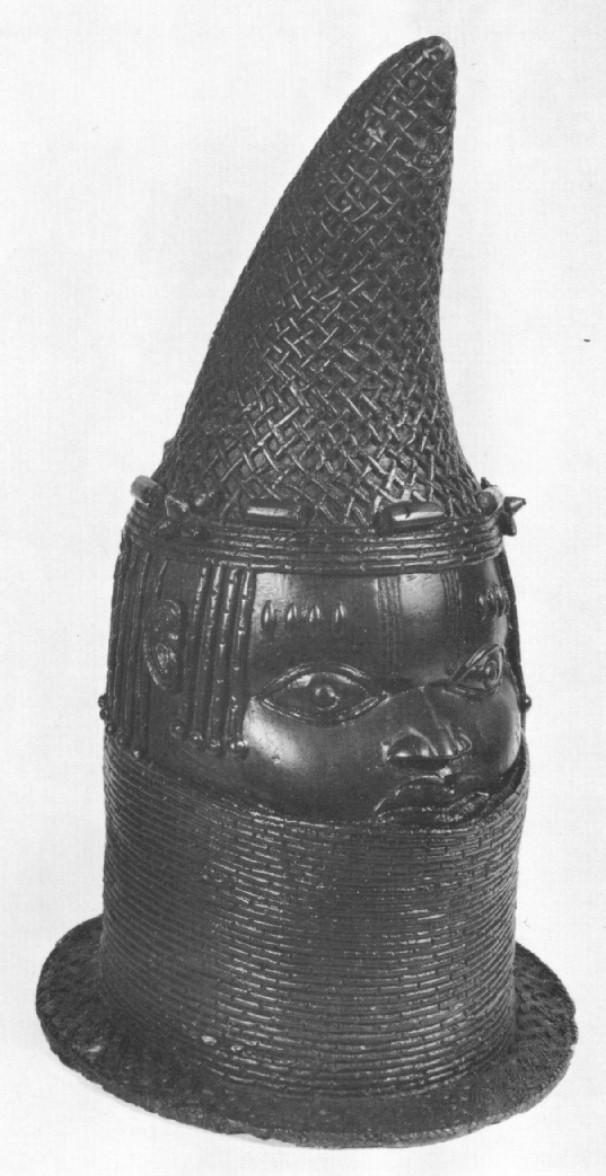

Igùn: Prototype X advances this inquiry by delving into text-to-three-dimensional rematerialization of the ukpe-okhue — a ceremonial variant of the Okuku (chicken's beak) hairstyle. Central to this investigation is the legendary Iyoba Idia (circa 1504–1550) whose unparalleled political and spiritual insights were instrumental to the military successes and territorial expansions that defined Benin's golden age (Egharevba, 1964). In recognition, Oba Esigie granted Idia the inaugural title of Iyoba (Queen Mother) and the singular right to design and wear the ukpe-okhue — a hairstyle adorned with design elements traditionally reserved for Obas. Mirroring the silhouette of a chicken's beak, the ukpe-okhue is distinguished by its towering, arched, conical shape, embellished with lattice-beaded red corals.

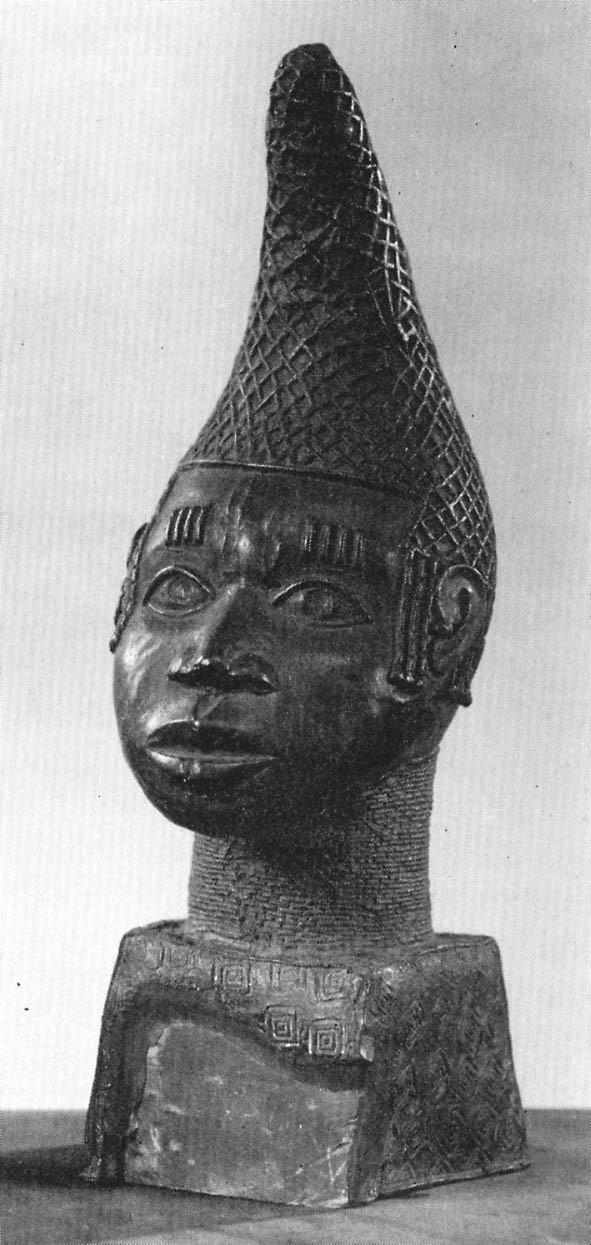

The title of "Iyoba" granted Idia unprecedented political authority and autonomy within a patriarchal state — a distinction not extended to royal women since the era of the Ogisos (Sky Kings), circa 1100 CE. Idia's elevated status is well-documented in Benin's 16th to 20th-century commemorative bronze sculptures, where the Iyoba and entourage are depicted as Benin's quintessential femme-presenting figures.

However, the devastation wrought by the 1897 British invasion culminated in the destruction of the Iyoba's palace and the cessation of the social/cultural privileges associated with the title (Egharevba, 1968). This discontinuity serves as the focal point for Igùn: Prototype X. In what ways did artists, the emerging elite, and anticolonial factions adopt/reject Idia's once-exclusive, state-sanctioned hairstyle during the artistic recession (1897-1914)? Was Idia's hairstyle represented in bronze-casted objects - if at all? Perhaps, these objects were designed as ancestral conduits for the masses and royalists (Osadolor, 2011) who formed an anticolonial resistance, seeking Idia's divine intercession? To what extent did non-royals who rose to prominence (Osadolor & Otoide, 2008) during the colonial occupation emulate Idia’s iconic hairstyle?

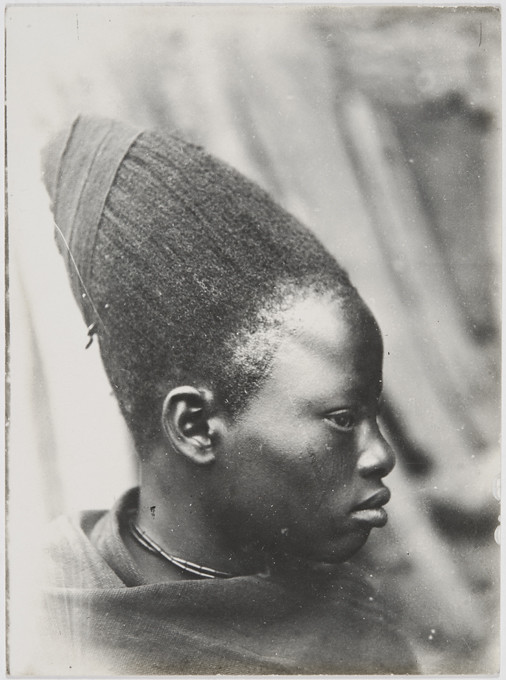

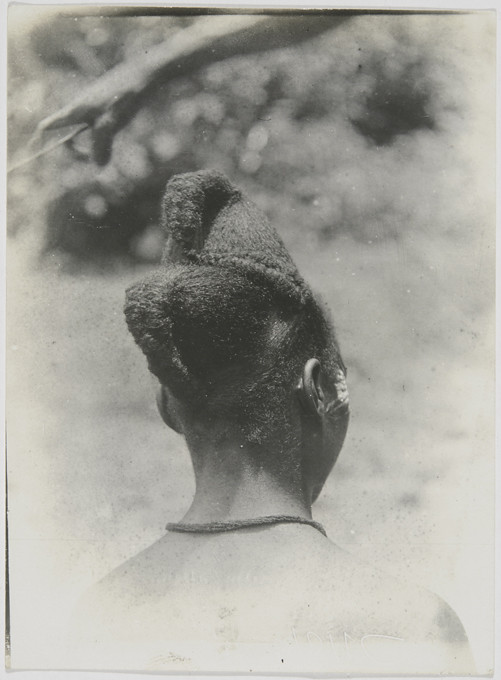

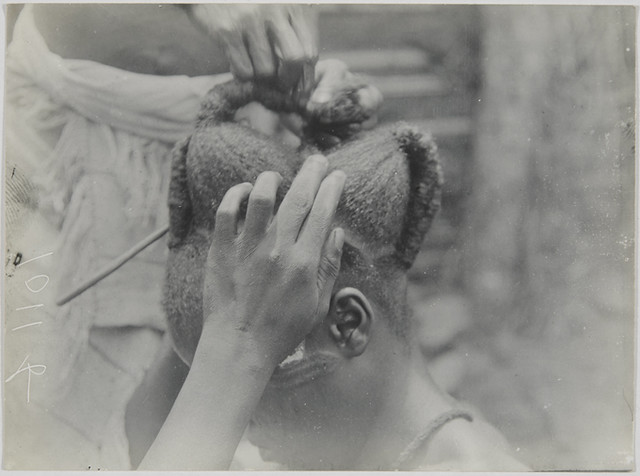

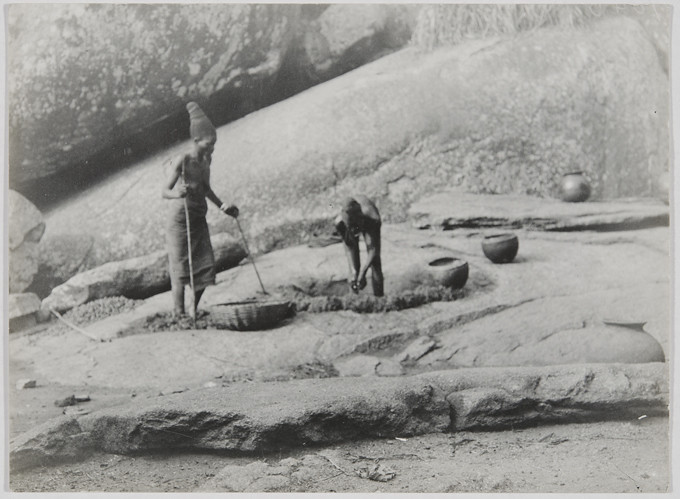

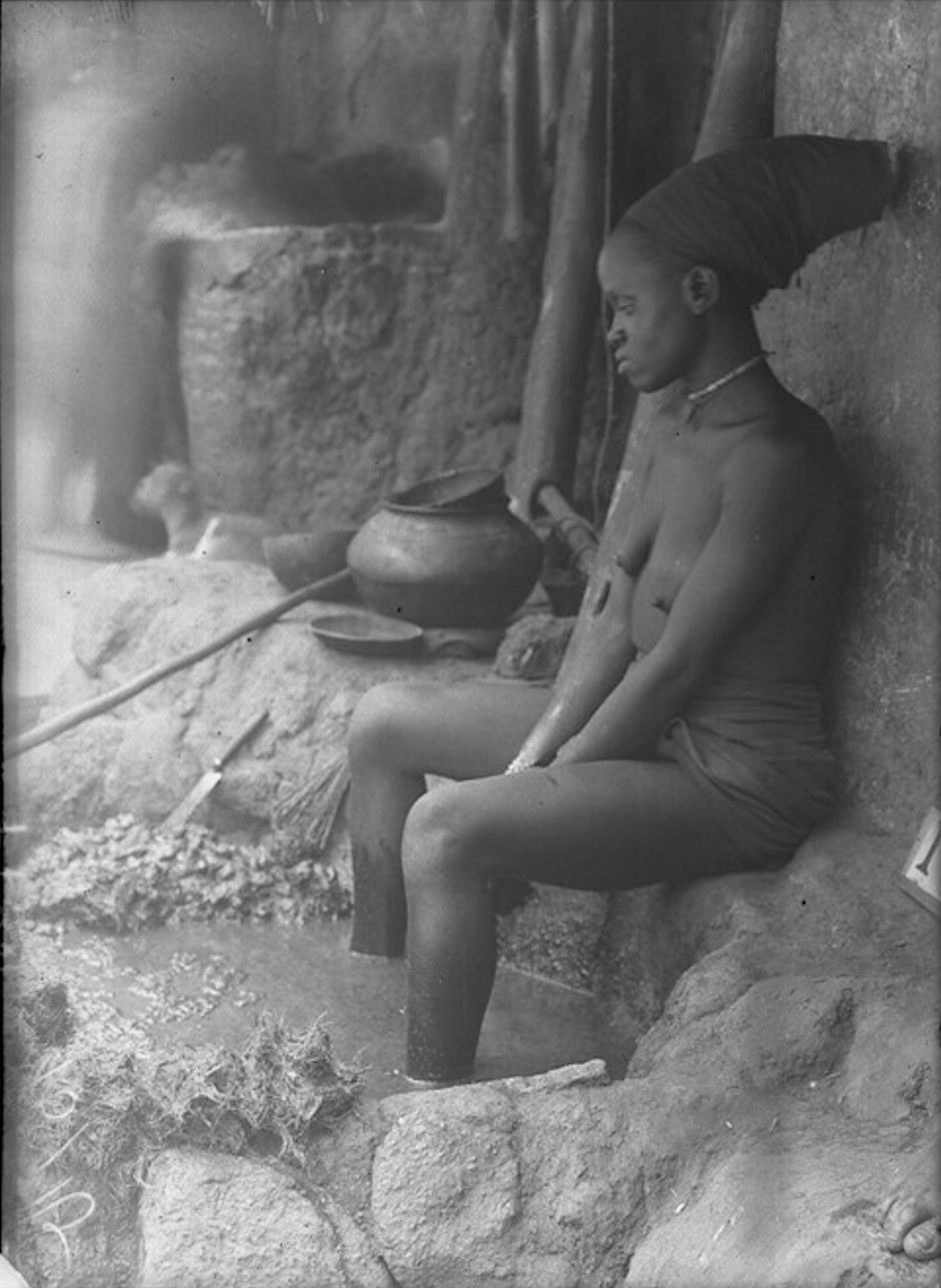

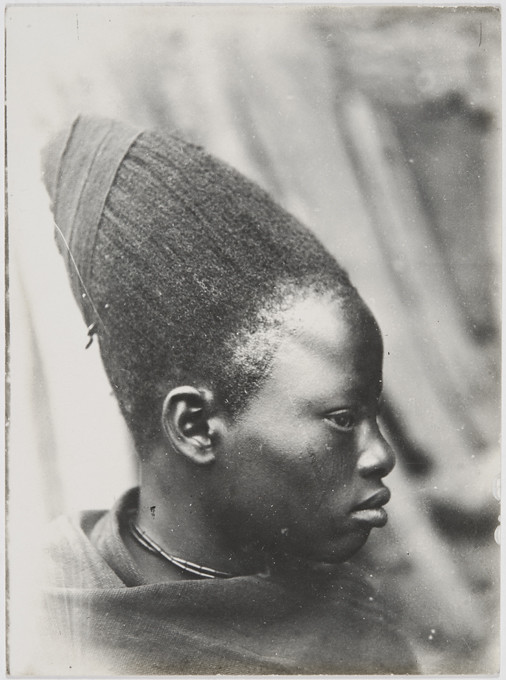

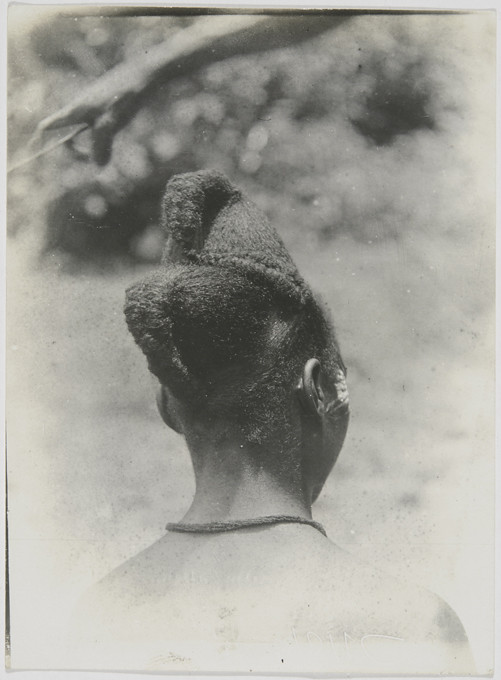

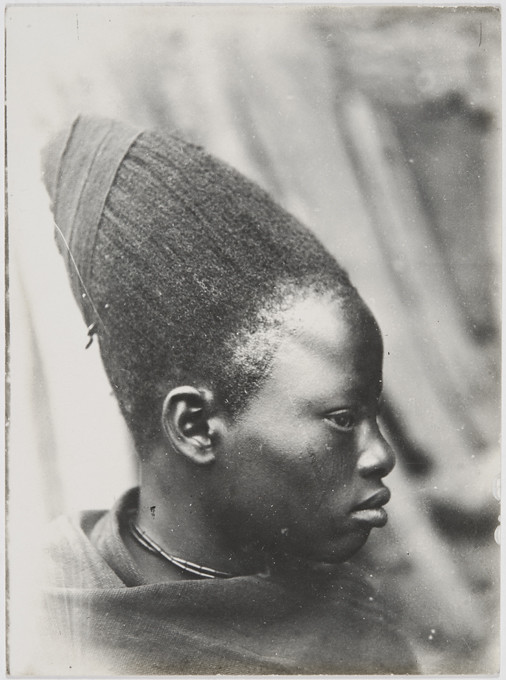

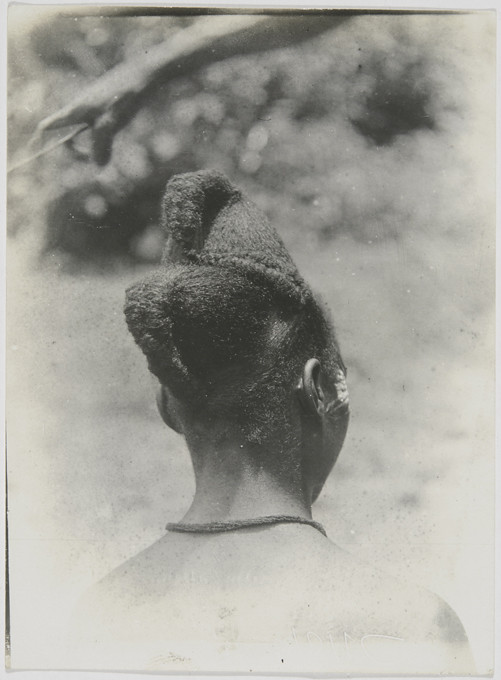

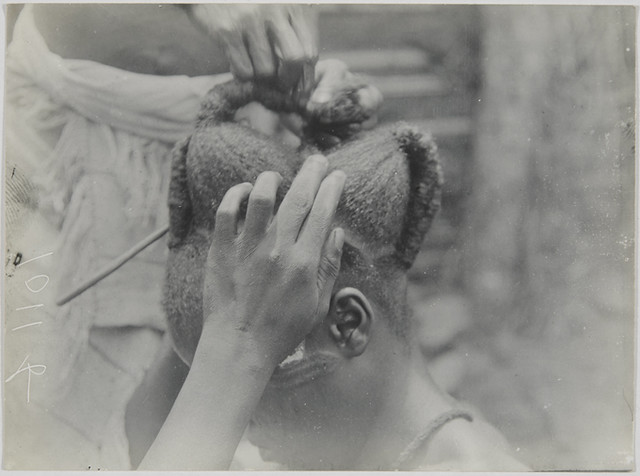

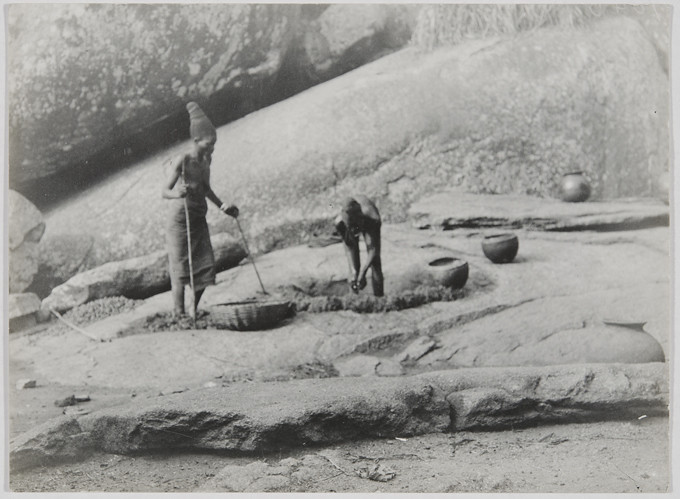

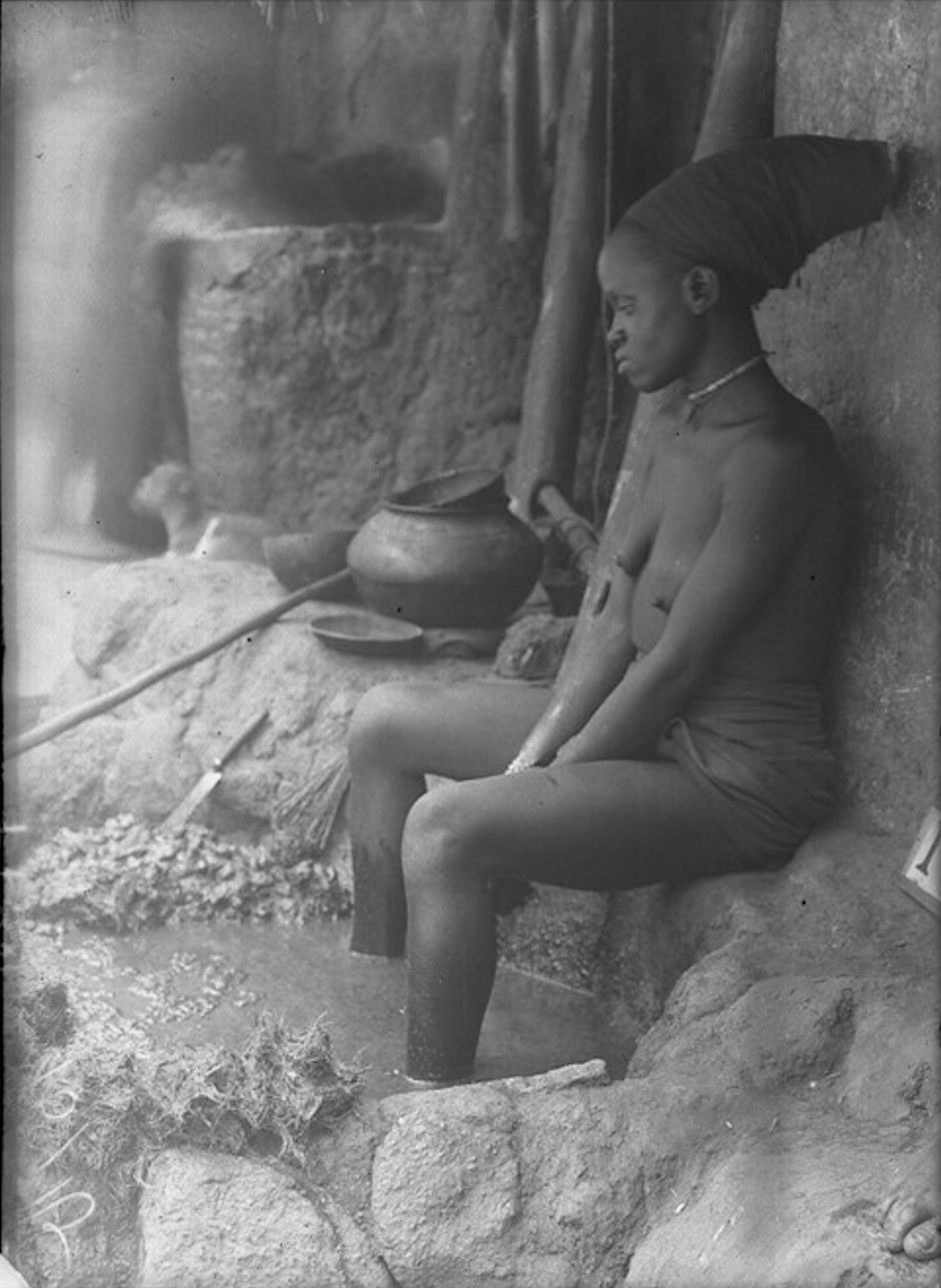

While little is known about sculptural production during the recession era, photographic evidence (c. 1909) suggests a shift: the Okuku hairstyle, once-exclusive to Iyobas, was adopted by non-royal Benin women in various configurations. This observation raises an additional question: In what ways might Benin artists of the recession era have envisioned and realized these royally unsanctioned Okukus?

In pursuit of answers, I utilized a text-to-3D algorithm to generate Benin Bronzes that showcase the Okuku hairstyle as it might have been envisioned by Benin artists during the artistic recession (1897-1914). The text prompts guiding this synthesis are based on variations of the Okuku seen in bronze-casted portraits of Iyobas (16th-19th centuries) and photographs of Benin women (1909-1915).

TECHNICAL NOTE

The 3D objects on this site were generated using a publicly available text-to-3D algorithm (dated: February 2024). The tool produced low-polygon models layered with medium-resolution textures. No modifications were made to the generated 3D geometries. Dynamic lighting and additional effects are applied in real-time via WebGL.

REFERENCES